It’s now 75 years since Soviet troops liberated the notorious death camp at Auschwitz and the vast majority of Holocaust survivors are no longer with us. The impact of continuing to research the Holocaust can, therefore, not be underestimated. The further away we move from the events and the more first-hand witnesses we lose, the more disconnected we feel, both individually and as a society.

As an archaeologist, I have experienced first hand how using a measured, scientific approach to the investigation of these atrocities can help to answer questions, heal communities, bring closure and allow for a more balanced approach to the representation of the subject.

The presentation of rigorously researched scientific evidence to support the known (and sometimes forgotten) history, has become ever more important at a time when this is being challenged by misinformation, competing narratives and populist movements.

As is the case for most British people, what I knew about the Holocaust was originally limited to what I had learned during secondary education and through my exposure to the subject in the media. I did not study the Holocaust at degree level or make a determined effort to develop a greater awareness. Now, through my work in the field of Holocaust archaeology I know different.

For my generation growing up in an age when the internet was just emerging, the information on the Holocaust was limited to academic research disseminated through school and traditional media. Today’s students have access to an unmanageable amount of material and the choice to search without restriction. But this access does not guarantee increased awareness or knowledge.

Recent surveys have suggested that one in 20 people in the UK don’t believe the Holocaust happened, while one-third of people from seven surveyed European countries know little or nothing about these events.

Additionally, a study of English secondary schools found that few students could accurately describe the events of the Holocaust, even though this is a compulsory part of the curriculum. This is a worrying trend for future generations.

Traditionally, Holocaust education has centred on historical sources and testimony from survivors. But – as these statistics show – new and innovative methods of collecting and presenting these facts are required to engage and, crucially, generate an awareness in people to ensure that these events are not forgotten or become rewritten. The use of an archaeological approach to research and present the Holocaust is therefore relevant and timely.

Our knowledge of the Holocaust tends to focus on the main camps rather than the tens of thousands of more diverse Holocaust sites across Europe. Many of these remain unprotected, understudied and known only to comparatively few people. Each of these sites contains individual stories which, when told, can illustrate direct relevance to our contemporary society.

Respecting remains

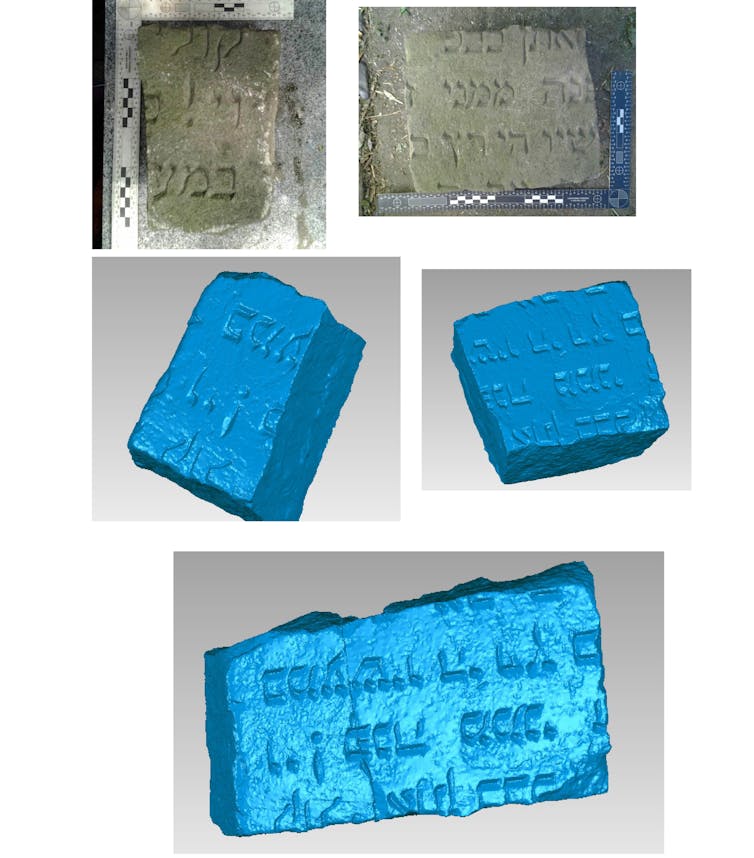

The practice of Holocaust archaeology, uses desk-based archival research, satellite imagery, aerial photographs, remote sensing, topographic survey and geophysical techniques to identify destroyed camps, lost killing sites and hidden mass graves. Importantly, these techniques avoid excavation that would disturb human remains, a practice which is forbidden under Jewish Law. Staffordshire University’s Centre of Archaeology, of which I am a member, has worked at more than 40 sites across Europe.

To provide an example, several killing sites and mass graves that were regarded as lost and under immediate threat have recently been identified by our team using these innovative archaeological methods. Sites in Rohatyn and across the regions of Vinnytsia and Zhytomir in the Ukraine, now have protected status and newly dedicated memorials to the victims.

Collected data can be visualised in a multitude of innovative ways with the primary objective being digital preservation, simplicity of access and increased awareness to a wide audience.

An emotional task

During my time on these projects, I have personally seen and been subject to the unequivocal evidence of the true scale of the Holocaust. I have experienced the profound effects of being presented with the graves and the remains of the victims and have seen the positive effects of presenting the evidence of the research to the public.

My experiences have been viewed through the eyes of someone who knew our modern history and was aware of the scale and effect of war – but I had no direct involvement in it. My archaeological background, however, meant I was more familiar with our ancient past than the generation that preceded me.

Working in this field, the effect on me has been thought-provoking and life-affirming. Put simply, I am more appreciative of the everyday opportunities and freedoms of life. I have been able to see the victims as individuals, whose lives and aspirations were cut short and whose memory should not be so easily manipulated or forgotten.

Many of these experiences would have been made all the more difficult without the collective support of my colleagues. The discussion that follows the analysis of victim testimonies, historic photographs and archaeological fieldwork is an important part of processing the raw reality of the Holocaust.

My work in this field has taken me to more than 15 sites across Europe, from Norway, Germany, the Czech Republic, Croatia to Poland and the Ukraine. It is evident that governmental and personal responses to the recognition and presentation of these sites vary in each nation. Holocaust denial and anti-Semitism is ever-present in the UK and across Europe more generally – and this is even more apparent at these sites. It is partly as a response to these continued pressures that these research projects are undertaken.

Raising awareness

There have, on many occasions, been causes to be pessimistic about human nature. I have encountered Jewish memorials that have been used for target practice, cemetery sites that have been historically and recently desecrated, and denial and hostility by local residents.

Distressingly, there have been several sites that have been looted, resulting in human remains, clothing and belongings being scattered across the surface, perhaps due to the misguided belief that mass graves contain items of value. These encounters highlight the fact that indifference and prejudices, but also social inequalities, are still prevalent.

Thankfully, positive events and achievements outweigh the bad. The grateful thanks of relatives, religious leaders and heritage groups, the raising of awareness within communities, schools and the media, and the identification of the exact boundaries of mass graves and camp buildings resulting in protection and memorialisation, are the successes to hold on to.

These projects also lead to the re-interment of remains. And, at sites that were erased by the Nazis, we were able to provide physical evidence relating to the nature of incarceration and extermination.

I am grateful to be in a position to continue to tell the story and get recognition for the sites that have been disturbed or neglected for decades. Helping to tell the stories of these lost individuals is especially important at a time when intolerance and indifference is becoming an accepted part of society.

The scale and extent of the devastation of the Holocaust means there is still much work to be done, especially given the current challenges of continued prejudice and misinformation.